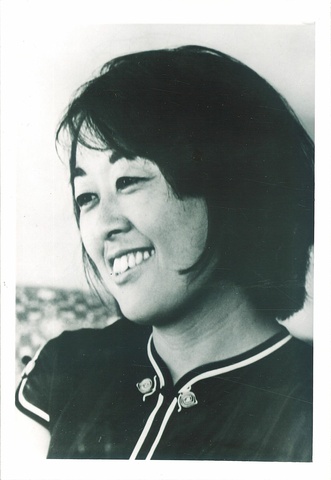

The death of Nieh Hualing Engle four months shy of her 100th birthday marks the end of a dynamic literary era. A prominent Chinese novelist, essayist, scholar, translator, editor, and author of more than thirty books, Ms. Engle co-founded the International Writing Program (IWP) in 1967 with the poet and writer, Paul Engle, who was the former director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and her second husband. They co-directed the IWP for the first ten years of its existence, earning a Nobel Peace Prize nomination for their success in bringing together writers from countries at odds with one another, particularly from the Soviet Bloc. Hualing, as she was known to writers from all around the world, directed the program for its next ten years, and after Paul died at O’Hare Airport in 1991, when they were en route to Poland to receive an award, she withdrew from advising IWP leadership until 1999, when the UI proposed to shutter the program, which had fallen on hard times. Fortunately, she decided to reengage before I arrived in 2000 to rebuild the IWP, and I came to value her counsel, particularly with regards to navigating the IWP’s complicated relationship to China—a task that has only grown more complex and necessary with each passing year.

Hualing’s insistence that we maintain the highest standards for the writers we select for the fall residency; her fierce commitment to literary excellence; her gift of hospitality; her resourcefulness; her interest in, well, everything; her sense of humor—these are what I treasure from having had the good fortune be in her orbit for nearly a quarter of a century. Hualing shaped my life and my directorship of the IWP with uncommon generosity, zeal, and love. Nor am I alone in feeling that. On one of the Nobel laureate Mo Yan’s return visits to Iowa City to pay his respects to her we took him to lunch at a Chinese restaurant downtown, where the waiters, busboys, and cooks kept sneaking peaks at the celebrity in their midst—a fact that Mo Yan repeatedly made light of in his resolve to celebrate his friend’s achievements. Here was a lesson in perspective, which is critically important for any writer. Hualing always knew who she was and what was what. She lived to the fullest her three lives, in China, Taiwan, and Iowa, and we are all the richer for it.

-Christopher Merrill, Professor of English and Director of the IWP

Loren Glass, M.F. Carpenter Professor and Chair of the English Department, writes, "In the introduction to their co-translation of the poetry of Mao Tse-Tung, Nieh Hualing and Paul Engle call Mao’s poetry “an intense political-military autobiography.” “Every poem,” they affirm, “has its immediate or distant connection with actual events in Mao’s share of recent Chinese history.” Then, in a simile that I’ve always felt describes their relationship to each other as much as it does Mao’s poetic method, they write, “In Mao, the politics and the poetry are like bands of muscle wrapped around each other; when one is flexed the other moves.

I like this line as a description of Hauling and Paul’s relationship, which was surely a marriage of true minds, a professional and personal partnership which sustained them both and enabled them to build Iowa City into a central node in the networks of world literature. But I also see it as a description of Hualing herself, whose writings constitute a personal witness to postwar world history unmatched in scale and scope. In her writing and her life, she entwined her exilic identity with historical events far and near; she was a true citizen of the world and will be mourned and remembered all around it."

-Loren Glass, M.F. Carpenter Professor and Chair of the English Department